Chamber Letter on Maine Privacy Bills

Re: LD 1973 and LD 1977

Dear Chairs Carney and Moonen:

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce (“Chamber”) appreciates the opportunity to provide comment on LD 1973, the “Maine Consumer Privacy Act,” and LD 1977, “the Data Privacy and Protection Act.” In today’s digital economy, it is critical that individual privacy protections enable continued innovation by which businesses can offer the products and services that consumers enjoy. LD1977 fails to meet these goals and would lead to an unworkable and anti-consumer patchwork of state laws. In addition, we also offer proposed suggestions to improve LD 1973 and proposed language to amend it.

Data privacy laws have a significant impact on small businesses. According to a recent Chamber report, Empowering Small Business, 75 percent of small businesses stated that technology platforms, such as payments apps, digital advertising, and delivery, help them compete with larger companies.[1] 73 percent of small businesses also say that limiting access to data will harm their business operations.[2] One small business owner of a coffee shop described the problems caused by blocking data usage[3]:

This is very unfortunate as it would essentially be another “pandemic” for us. Not having customer data means that we would go back to the early 1980’s where we would market our products to a generic list, which in turn would be extremely costly and not a good customer experience. Having customer data helps us customize our marketing so the end result is more meaningful to the customer.

Consistency, uniformity, and workability are critical to ensuring small businesses are not disproportionately harmed by data protection laws.

I. LD 1977

A. LD 1977 Exacerbates a State Patchwork

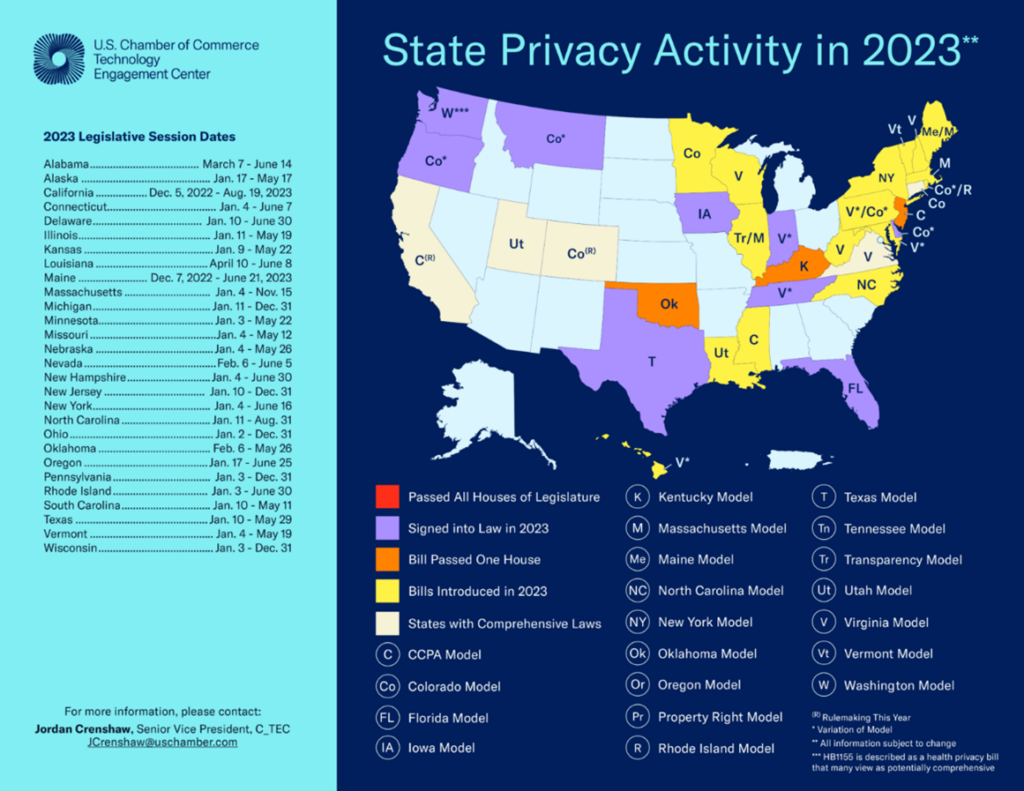

LD1977 would significantly harm innovation and lead to an unworkable patchwork of state laws. Thirteen states have passed comprehensive privacy legislation since 2018. Fortunately, twelve of these states, with legislatures controlled by both Democrats and Republicans, such as Virginia, Oregon, Texas, and Colorado have passed similar laws using a “Consensus Framework” that provides strong consumer protections and enables innovation[DM1] .[4] LD 1977 significantly departs from this Consensus Framework that has emerged across the nation, imposing prohibitions that limit sensitive data collection to what is “strictly necessary,” AI risk assessments, and utilizing private rights of action as an enforcement mechanism.

Absent a federal privacy law, it is critically important that states adopt harmonized and uniform standards for privacy. A recent report from ITI highlighted that a national patchwork of privacy laws would cost the United States economy $1 trillion and disproportionately impact small businesses with a $200 billion economic burden.[5] As stated in Empowering Small Business, a majority of small businesses are concerned that a patchwork of laws will increase both their compliance and litigation costs.[6]

B. LD 1977 Has Conflicting Requirements

Section 9615 requires covered entities to conduct impact assessments of algorithms. These impact assessments would require companies to examine “disparate impact on the basis of an individuals’ race, color religion, national origin, sex, or disability status.” Section 9605 though, bars the collection or processing of “sensitive data, except when the collection or processing is strictly necessary to provide or maintain a specific product or service…” Under LD 1977, race, color, ethnicity, and religion are considered “sensitive data.” Given then definition of “sensitive data,” covered entities could be faced with the choice of violating the bill to either comply with the bill’s data minimization or impact assessment requirements.

C. Private Rights of Action

Maine should harmonize its legislation with the thirteen other states that have rejected private rights of action for privacy violations. Privacy legislation should be enforced by state attorneys general and not empower the private trial bar at the expense of business innovation and viability. Frivolous, non-harm-based litigation, in particular, has been used in the past to extract costly settlements from companies, even small businesses, based on privacy law provisions granting a private right of action. Private rights of action are ill-suited in privacy laws because:[7]

- Private rights of action undermine appropriate agency enforcement and allow plaintiffs’ lawyers to set policy nationwide, rather than allowing expert regulators to shape and balance policy and protections. By contrast, statutes enforced exclusively by agencies are appropriately guided by experts in the field who can be expected to understand the complexities of encouraging compliance and innovation while preventing and remediating harms.

- They can also lead to a series of inconsistent and dramatically varied, district-by-district court rulings. Agency enforcement can provide constructive, consistent decisions that shape privacy protections for all American consumers and provide structure for companies aiming to align their practices with existing and developing law.

- Combined with the power handed to the plaintiffs’ bar in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23, private rights of action are routinely abused by plaintiffs’ attorneys, leading to grossly expensive litigation and staggeringly high settlements that disproportionally benefit plaintiffs’ lawyers rather than individuals whose privacy interests may have been infringed.

- They also hinder innovation and consumer choice by threatening companies with frivolous, excessive, and expensive litigation, particularly if those companies are at the forefront of transformative new technologies.

Private rights of action would be devastating for business because individual judicial district precedent could also create further confusion and conflict.

II. LD 1973

The Chamber recognizes that LD 1973 more closely resembles the bipartisan Consensus Framework that has already passed in twelve states. We have listed below commentary on how proposed changes to LD 1973 would depart from state Consensus Framework and how that could limit innovation and the products and services consumers enjoy.

- Definition of Sensitive Data. It has been proposed that the definition of “Sensitive Data” include “Online usage information derived from the consumer’s use of a controller’s online product or service, including but not limited to web browsing history and search data, content of communication, device and or online identifiers (e.g. MAC address, IP addresses, etc.).” This would significantly impact e-commerce in Maine, as basic internet functionality and advertising would be subject to strict opt-in requirements.

- Opt-In. Like the 14-state consensus laws, consumers should have the right to opt-out of targeted advertising, profiling, and data sales. A differing requirement that companies obtain consent before engaging in these types of activities could be harmful to societally beneficial uses of data and small business. 65 percent of small businesses have stated that losing the ability to conduct targeted advertising would harm their business.[8] Additionally, an opt-in regime will subject consumers to notice fatigue as was experienced during the implementation of Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation.

- “Strictly Necessary” Data Minimization Standard. The 14-state consensus approach does not limit data usage and collection to what is “strictly necessary.” Such an approach would significantly inhibit innovation as covered entities may have new societally and consumer-friendly business uses for data throughout different times of product and service development.

- Applicability to Small Business. All states that have adopted comprehensive privacy legislation have attempted to reduce burdens on small businesses by limiting their laws applicability to covered entities to collect or use the data of a certain number of individuals. As discussed previously, small businesses will bear a disproportionate burden. We suggest that states adopt a threshold like California and Virginia’s laws of 100,000 individuals. It is also important to note that even if the smallest businesses are not directly covered by legislation, tools they use to compete would still be subject to state regulations and a patchwork.

- Automatic Deletion. LD 1973 would require companies to delete data used for targeted advertising, sales or transfers unless they have obtained consent. Such an automatic deletion requirement is not a provision in the 14-state consensus model that has been adopted. Such a requirement would once again subject consumers to notice fatigue as companies would be required to obtain consent to retain the data previously collected.

- Industry neutrality. Every state that has adopted a comprehensive privacy law has recognized the importance of ensuring that the same data is subject to the same protections regardless of where it exists and is processed in the internet ecosystem. Current Maine law does not reflect industry neutrality due to its disparate treatment of internet service providers (ISPs). As introduced, LD 1973 repeals the ISP privacy law and comprehensively applies the same requirements to every industry sector.[9] We support this approach and ask you to align consumer protections in LD 1973 with those in the Consensus Framework.

- Enforcement. LD 1973 as introduced strikes the right balance by vesting enforcement authority with the Attorney General. For the reasons stated above, we would oppose inclusion of a private right of action. We also believe that in order to encourage collaborative compliance, privacy legislation should provide for a 30-day cure period.

We once again thank you for the opportunity to comment. For the reasons stated above to protect privacy, encourage innovation, and prevent an unworkable state patchwork, we oppose LD 1977 and encourage you to focus on passing LD 1973 and harmonize it with existing state privacy laws.

Sincerely,

Jordan Crenshaw

Senior Vice President

Chamber Technology Engagement Center

U.S. Chamber of Commerce

[1] https://americaninnovators.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Empowering-Small-Business-The-Impact-of-Technology-on-U.S.-Small-Business.pdf.

[2] Id.

[3] https://www.uschamber.com/technology/small-business-owners-credit-technology-platforms-as-a-lifeline-for-their-business (emphasis added).

[4] https://americaninnovators.com/2023-data-privacy/.

[5] https://itif.org/publications/2022/01/24/50-state-patchwork-privacy-laws-could-cost-1-trillion-more-single-federal/.

[7] https://instituteforlegalreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Ill-Suited_-_Private_RIghts_of_Action_and_Privacy_Claims_Report.pdf

[8] Supra n. 1.

[9] Title 35-A M.R.S. § 9301.

I added “Fortunately” on the assumption we like the 12 who used the consensus framework. Change back if I’m wrong. [DM1]

The Weekly Download

Subscribe to receive a weekly roundup of the Chamber Technology Engagement Center (C_TEC) and relevant U.S. Chamber advocacy and events.

The Weekly Download will keep you updated on emerging tech issues including privacy, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, transportation, and government digital transformation.