State Data Privacy

Download the 2024 Data Privacy Map

Georgia

SB473(Albers)—The Georgia Consumer Privacy Protection Act mirror Tennessee’s privacy law which provides Virginia’s protections but allows companies to use compliance with the NIST Privacy Framework as an affirmative defense. The bill has limited exemptions and does not explicitly prevent a private right of action. This bill passed the Senate on February 27 by a vote of 37 to 15.

Hawaii

SB974 (Lee)/HB1497 (Saiki)[c]—This bill mirrors the Virginia model. A second amended version of SB974 passed the Hawaii Senate 23 to 1 to 1 on March 7, 2023.

SB21 (Rhoads) — This bill would amend Hawaii’s Constitution to grant citizens an exclusive property right on data generated on networks like the internet.

SB1180 (Lee) — This bill would require consent before internet browser history is sold and places limits on geolocation data.

SB3018(Lee)—This bill mirrors the Colorado law but requires opt-in for sales and targeted advertising for known children between 13 and 16.

Illinois

HB1381 (Bucker) / SB1365 (Halpin) — The Right to Know Act would require companies to disclose information sharing practices and have a data protection safety plan in place. Violations would be enforceable by a private right of action.

HB3385 (Rashid)[c]—This bill is the Massachusetts Data Privacy and Protection model.

HB5581(Huyhn)—The Illinois Privacy Rights Act mirrors the Colorado law but lacks rulemaking authority.

SB3517(Rezin)—The Privacy Rights Act mirrors the California Privacy Rights Act.

Kentucky

HB15(Branscum)—This model is the Virginia model. It has passed both the Kentucky House and Senate

unanimously.

HB24(Pratt)—This bill follows the Utah model.

SB15(Westerfield)—This bill is the Kentucky model. Although it has many of the same consumer rights as Colorado’s law, it gives consumers the right to opt out of “tracking” which is the combining of data across commonly branded websites and a third party. Companies would be required to follow a global opt-out for tracking, sales, and targeted advertising. The bill would also require companies upon Attorney General investigation to turn over the specific third parties with whom they share information. Much like other state laws that require companies to disclose to consumers the categories of third parties with whom they share data, this bill would require additional disclosures like the location where date is stored. Data is not allowed to be processed for targeted advertising or tracking of minors. Sensitive data may not be processed without giving consumers the right to opt out. The Attorney General has exclusive authority to enforce the bill, but consumers can still utilize remedies from other laws. A similar bill passed the Senate last year.

Maine

SP807/LD1973(Keim)[c]—This bill is the Maine model. It effectively follows Colorado’s approach but has an opt-in consent requirement for data sales, targeted advertising, and profiling. This bill has been the focus of a Joint Standing Judiciary Committee review over the later part of 2023. The Chamber sent a letter recommending ways to harmonize this approach with other state laws on December 18, 2023. A Work Session was held on January 18 comparing this and LD1977.

LD1977/HP1270 (O’Neil)[c]—This bill is effectively the Massachusetts Data Privacy and Protection model. This bill has been the focus of a Joint Standing Judiciary Committee review over the later part of 2023. The Chamber sent a letter opposing this bill because of its conflict with other state laws on December 18, 2023. A Work Session was held on January 18 comparing this and LD1973.

SP646(Brakey)[c]—A constitutional amendment has been proposed for a “natural right to personal privacy.”

Maryland

SB541(Gile)/HB567(love)—This bill mirrors Connecticut’s updated privacy law in many ways but also incorporates stricter requirements like data minimization for what is strictly necessary, opt-in for targeted advertising, bans on selling sensitive data, prohibitions on selling personal data of or processing data for targeted advertising of teens. Given the differences, this will be called the Maryland model. On March 7, the Senate version was reported by the Senate Finance Committee. The House version passed 105 to 32. The Senate version passed 46 to 0.

Massachusetts

S25(Creem)/H83(Vargas)[c]—The “Massachusetts Data Privacy Protection Act” effectively mirrors the American Data Privacy and Protection Act of the 117th Congress. The Joint Committee on Advanced Information Technology, the Internet and Cybersecurity held a hearing on this bill on October 19, 2023. As this is the first state to consider this approach, it is the “Massachusetts Data Privacy and Protection Model.”

H60(Carey)/S227(Finegold)[c]—The “Massachusetts Information Privacy and Security Act” would among other things restrict the processing of data to certain lawful basis and would give consumers the right to opt out of data sales and targeted advertising. The bill also has portability and deletion rights for consumers. The bill would also prohibit discrimination based on a consumer exercising their privacy rights. The bill would require data broker registration. Companies would be prohibited from processing data in a discriminatory manner. The bill would be enforced by the Attorney General and a private right of action for data breaches. The Joint Committee on Advanced Information Technology, the Internet and Cybersecurity held a hearing on this bill on October 19, 2023.

Minnesota

SF2915 (Westlin) / HF2309 (Elkins) — The “Minnesota Consumer Data Act” is effectively the Colorado model. One notable difference is that both Colorado and Minnesota provide for an opt out of profiling. Consumers in Minnesota are given the ability to question the result of automated profiling. A new version of the bill was released on February 26, 2024 which bars a private right of action, and creates universal opt-out for data sales and targeted advertising. If consumer make rights requests, companies are also required to indicate to the consumer if they hold enumerated types of personal information. The bill also exempts small businesses defined as such by the Small Business Administration, and does not require Minnesota-specific privacy notices if they comply with the substance of the law. Given the changes to the bill, it is now the Minnesota model. SF2915 has also been reported favorable out of the Commerce and Consumer Protection Committee. The House version was reported out of the State and Local Government & Finance Committee on March 14.

HF1367 (Noor) — This bill is effectively the CCPA with a private right of action.

Michigan

SB659(Bayer)—This bill, known as the “Michigan Model” has many of the Virginia protections like deletion, opt-out, correction, and access rights. The bill also is an opt-in approach to all personal data processing. Processing for targeted advertising and sales are banned for consumers between 13 and 18. Covered entities would also have transparency requirements concerning automated profiling. The bill would be enforced by the Attorney General as well as private rights of action.

Missouri

SB731(Rowden)—This bill mirrors the Utah model.

Nebraska

LB1294(Bostar)—This bill mirrors the Virginia approach but has a small business exemption in line with the Texas model that refers to the Small Business Administration.

New Hampshire

SB255(Carson)[c]—This bill is effectively the Virginia model. The bill passed the Senate on March 16, 2023. On November 8, 2023, the House Judiciary Committee recommended passage with amendments including a clearer prohibition on private rights of action and a 60-day cure period. A final version was passed and is awaiting the Governor’s signature. This bill was signed by the Governor on March 6.

New Jersey

A1971 (Mukherji) S332 (Singleton) [c]—This bill effectively started as a CCPA-model for online operators. The bill passed the New Jersey Senate in February 2023 and has since morphed into a bill more like Colorado’s privacy law. On December 21, 2023, floor amendments were passed in both the House and Senate. Like Colorado, the floor amendments have rulemaking authority for the Attorney General. Unlike Colorado, the bill would add automated profiling to the list of data processing subject to universal opt-out. The amendments also do not explicitly bar all private rights of action under other laws. While technically a carry-over bill from 2022, there is a possibility this bill is voted upon for passage on January 8, 2024, the last day before the 2024-2025 legislation cycle beings. This bill is the “New Jersey Model.” This bill passed both the Assembly and Senate (21-14) on January 8. It is now with the Governor. Senator Singleton has reintroduced a version of this S1389 which prevents a private right of action under any other law in New Jersey.

S2062(Gopal)— The “New Jersey Disclosure and Accountability Transparency Act (NJ DaTA)” would bar the processing of personal information unless there is an enumerated legitimate interest or there is opt-in consent. The bill also provides for security requirements in addition to access, correction, and transparency rights. Individuals also have the right to object to processing in certain circumstances. Consumers have the right to opt out of having decisions be made solely by automated decision making. The bill has a 72-hour data breach notification requirement. The Office of Data Protection and Responsible Use in the Division of Consumer Affairs in the Department of Law and Public Safety is responsible as a rule maker, clearinghouse, and enforcer of the Act.

New York

S365 (Thomas)/A7423(Rozic)[c]—The “New York Privacy Act” incorporates the amendments of the 2022 New York Privacy Act legislation. The Senate on June 8, 2023, passed the bill 44 to 18. The current version now resembles the Colorado law but also has a data broker registry and expands universal opt-out to include automated profiling. Given these changes this bill is the “New York Model.”

S2277 (Kavanagh)/A3308(Cruz)[c]—The “Digital Fairness Act” would require a short-form privacy notice, require “freely given, specific, unambiguous opt-in consent” to process personal information and for any changes made to the processing. The bill would bar refusal of service based on exercising privacy rights. It would require a duty of care based on adequate industry standards for things like storage and transmission. The bill would also require a written policy on things like biometric retention and bar the activation of microphones and video devices to obtain biometrics without consent. The bill would also ban discrimination through data processing and targeted advertising as well as require automated decision-making impact assessments. The bill would be enforced by a private right of action.

S3163 (Hoylman)[c]—The “Right to Know Act” would provide consumers with the ability to request how companies collect, use, and share personal information.

S3162(Hoylman)[c]—This bill effectively mirrors CCPA.

S4940(Parker)[c]—This bill would amendment New York’s Constitution creating a right to privacy.

A4374(Gunter)[c]—This bill would give consumers the right to know categories of data processed by companies and give them the right to opt out of data sales. Consumers would be able to use a private right of action to sue for damages.

S5555(Comrie)[c]—The “It’s Your Data Act” provides for transparency, access rights, and requires opt-in consent to collect or share personal information. The bill would be enforced by the Attorney General, district attorneys, and city corporate counsel. The Attorney General would have rulemaking authority.

S5662(Gounardes)[c]—The “Data Economy Labor Compensation and Accountability Act” creates an Office of Consumer Data Protection governed by a seven-member board. The Office is empowered to promulgate any rules necessary for consumer data protection. Controllers and processors would have to register with the State.

A6319(Solages)[c]—This bill is the Massachusetts model and effectively copies the “American Data Privacy and Protection Act.”

North Carolina

S525(Salvador)[c]—The “North Carolina Consumer Privacy Act” is a slimmed down version of the Virginia legislation. It requires a privacy policy as well as consumer rights to access, deletion, and opt out of targeted advertising. Consumers must be given notice of processing of sensitive data and the ability to opt out. Discrimination based on the exercising of privacy rights is prohibited. The Attorney General has exclusive authority to enforce.

Ohio

HB345(Hall)[c]—The Ohio Personal Privacy Act would require businesses to have a privacy notice and policy. Material changes to the policy would require affirmative consent from consumer. The bill also has correction, portability, and deletion rights. Consumers have the right to opt out of processing for targeted advertising and data sales. There is a prohibition on discriminating against consumers for exercising privacy rights. The Attorney General has exclusive enforcement rights and there is an affirmative defense based on the NIST privacy framework.

Pennsylvania

HB1201 (Neilson)[c]—The “Consumer Data Protection Act” mirrors the Colorado model. The bill was amended on December 13, 2023, to bring it further in harmonization with the Colorado model. This bill passed the House on March 18 139-62.

HB708(Kenyatta)[c]—This bill mirrors the Virginia model.

HB1947(Mercuri)—The Consumer Data Privacy Act in substance mirrors the Virginia approach but there is broad rulemaking authority for the Attorney General who would primarily enforce the bill. Violations trigger the states consumer protection laws which have a private right of action.

Rhode Island

H7787(Shanley) | S2500(DiPalma)—This bill mirrors the Virginia model.

South Carolina

HB4696(Guffey)—This bill mirrors the Florida privacy law and is limited to a small subset of technology companies.

Vermont

H121 (Marcotte)[c]—This bill would require “data collectors” to minimize the use, retention, collection, and sharing of personal information. The bill would also define a “Data broker” as a business, or unit or units of a business, 18 separately or together, that knowingly collects and sells or licenses to third 19 parties the brokered personal information of a consumer with whom the 20 business does not have a direct relationship.

The bill would also give broad rulemaking authority for personal information regulation to the Attorney General. Data collectors are brokers would have to honor universal opt out requests for targeted advertising, predictive analytics, tracking, or the sale of personal information. The bill would also require data breach notices for data brokers. Data broker registration would also be required. Individuals would also be able to request data brokers stop collecting data, delete data, and stop selling data. The bill also has regulations around biometrics. The Attorney General has sole enforcement.

SB259(Clarkson)—This bill mirrors the Colorado approach and provides opt-in for teens 13 to 16 for targeted advertising and data sales. There is also a data broker registry and data breach section.

Washington

SB5643(Hasagawa)/HB1616(Kloba)[c]—This bill has incredibly low thresholds for covered entities. It would apply to companies that have $10 million in annual revenue through at least 300 transactions OR those that have the data of 1,000 or more individuals. The bill would also give consumers transparency, access, opt-out for “nonessential” data processing, correction, and deletion rights. Consumers would also be given the right to be free of “surreptitious surveillance.” Notice requirements include a long- and short-form privacy notice which includes among other things how data is monetized.

The bill effectively follows an opt-in consent model for “captured data.” Companies may not discriminate against individuals for exercising their opt-in consent rights. The bill would require industry standard cybersecurity practices at companies. Covered entities are prohibited from disclosing “captured personal information” to third parties unless there is a contract with third parties who have the same obligations as a covered entity. Covered entities are forbidden from activating devices like microphones, cameras, or sensors without notice and opt-in consent.

The bill would also bar processing data, targeted advertising, using facial recognition, or Artificial Intelligence to discriminate against protected classes in employment, insurance, finance, healthcare, credit, housing, or education opportunities or public accommodations. The bill will also require data protection assessments.

The bill authorizes private rights of action and bars contractual pre-dispute arbitration. Children 13 and over would be able to represent their own rights under the bill.

As this bill was reintroduced with identical language, it will be known was the “Washington Model.”

HB2277(Kloba)—This bill creates a data brokery registry for a very broad definition of “data brokers.” Effectively, FCRA and financial services entities could be the only entities exempted.

West Virginia

HB5698(Linville)—The Consumer Data Protection Act mirrors the Virginia model. The House Infrastructure and Technology Committee has recommended passage.

HB5118(Young)—This bill follows the CCPA model with a right to correction.

Wisconsin

AB466(Zimmerman)SB642 (Quinn)—This bill follows the Virginia model. It passed the Assembly on November 14.

Summary Designations

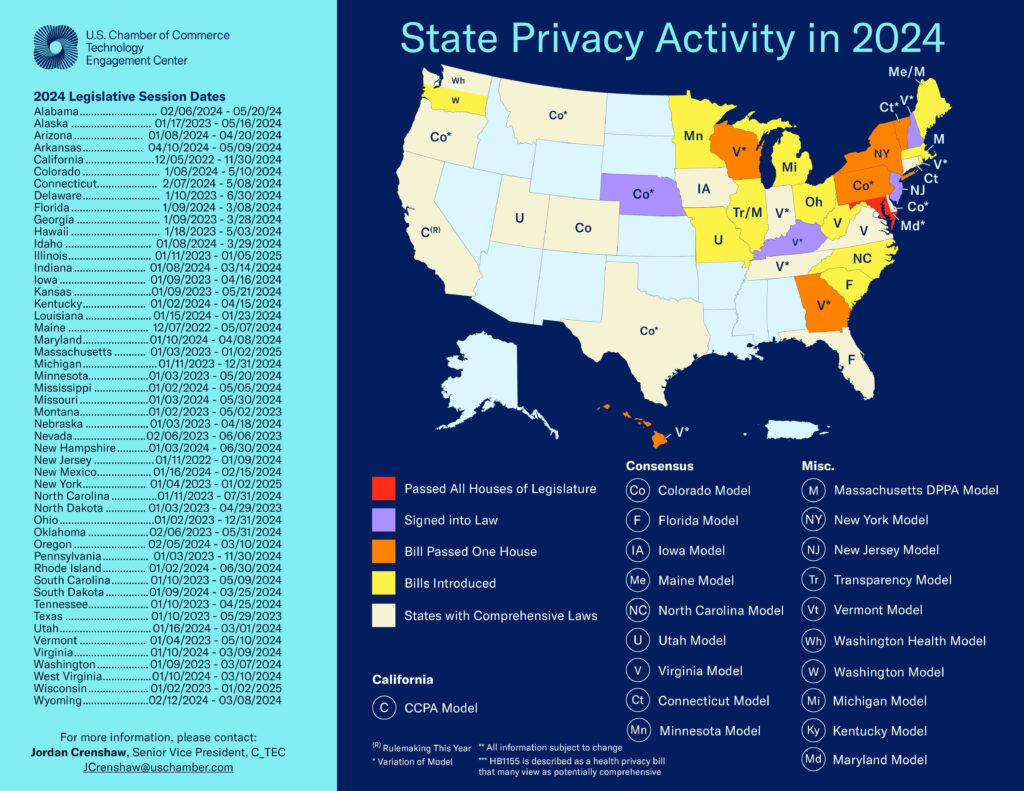

Although there are multiple models indicated on C_TEC’s heat map, there are currently five models that have passed in state legislations:

- CCPA Model (C) — This model includes access, deletion, and opt out rights for data sales. It also includes anti-discrimination provisions for exercising consumer rights and provides a private right of action for data breach-type incidents.

- Virginia Model (V) — This model includes access, correction, deletion and opt out rights for processing that has a legal result, targeting advertising, or data sales. Opt-in is required for sensitive data processing and there are data processing limitations. The law also requires impact assessments. There is no private right of action, and the Attorney General is the primary enforcer.

- Colorado Model (Co) — This model is similar to the Virginia model but includes rules around dark patterns and global opt out mechanisms.

- Connecticut Model (Ct)—Originally, this model is similar to Colorado’s law but 2023 amendments now include protections for “consumer health data,” prohibitions on certain processing for minors, and social media account deletion.

- Utah Model (U)—This model mirrors the Virginia model in several ways although it does not provide opt out rights for profiling that creates a legal result or impact. The bill also does not require impact assessments.

- Iowa Model (IA)—This model mirrors the Utah model but does not have a right to opt out of targeted advertising.

- Florida Model (F)—This model requires consent for the use of geolocation data as well as information obtained through the operation of a voice recognition features. Search engines are required to provide consumers with information on how their algorithms prioritizes or deprioritizes political partisanship or ideology. Controllers must have a privacy policy. The bill has deletion, correction, access rights and rights to opt out of sales and sharing. The bill also bars discrimination against consumers for exercising their privacy rights. Generally, this bill is targeted toward larger online, ad-driven companies.

- Washington Model (W)—Although not described as a comprehensive privacy law, due to its broad definition of “consumer health data,” some have argued it could effectively function as one. The model would require regulated entities to provide notice of data practices and would require consent for collection and sharing of consumer health data. The bill also grants deletion rights for consumer health data and restricts the types of employees and processors that can have access to it. The bill also bans certain geofencing about health care services. A violation of the Act is considered an unfair and deceptive practice under Washington law subjecting regulated companies to a private right of action.

The Weekly Download

Subscribe to receive a weekly roundup of the Chamber Technology Engagement Center (C_TEC) and relevant U.S. Chamber advocacy and events.

The Weekly Download will keep you updated on emerging tech issues including privacy, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, transportation, and government digital transformation.