Congress Should Write Privacy Rules, Not the FTC

This week, President Biden nominated Alvaro Bedoya, privacy activist and head of Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology, to replace outgoing Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Commissioner Rohit Chopra. Just two days later, the Commission by a 3-2 vote adopted a policy statement extending privacy notification requirements for some health apps and connected devices. In a dissenting statement, Commissioner Noah Phillips asserted that the Commission’s new policy “end runs not one but two ongoing rulemaking processes and relies on a convoluted interpretation to apply civil penalties to a broad swatch of conduct never contemplated by Congress.”

These privacy developments are not isolated but are a continuation of a broader series of actions that circumvent Congress and transparency principles:

- In July, the White House issued its Executive Order on Competition, calling on the FTC to conduct a rulemaking about data privacy.

- Meanwhile, the FTC held its first “open meeting,” in which it listened to public comment after voting on a measure to consolidate and streamline its Magnusson-Moss Rulemaking authority to the Chair. Magnusson-Moss Rulemaking by Congressional design is intentionally slow to prevent out-of-control regulation. The minority Commissioners objected to these procedural changes on the grounds that they “undercut the independence of those charged with conducting evidentiary hearings, limit valuable input from the public, and reverse decades of practice regarding agency transparency.” Conversely, in that very same open meeting, Commissioner Slaughter called for using the new procedures to “tackle cutting edge issues like data…” She has also this summer proposed that the FTC regulate artificial intelligence.

- Finally, this week, the House Energy & Commerce Committee approved a proposal in the $3.5 trillion partisan reconciliation package that would create a new $1 billion privacy and data enforcement bureau—without ever having passed a comprehensive privacy law.

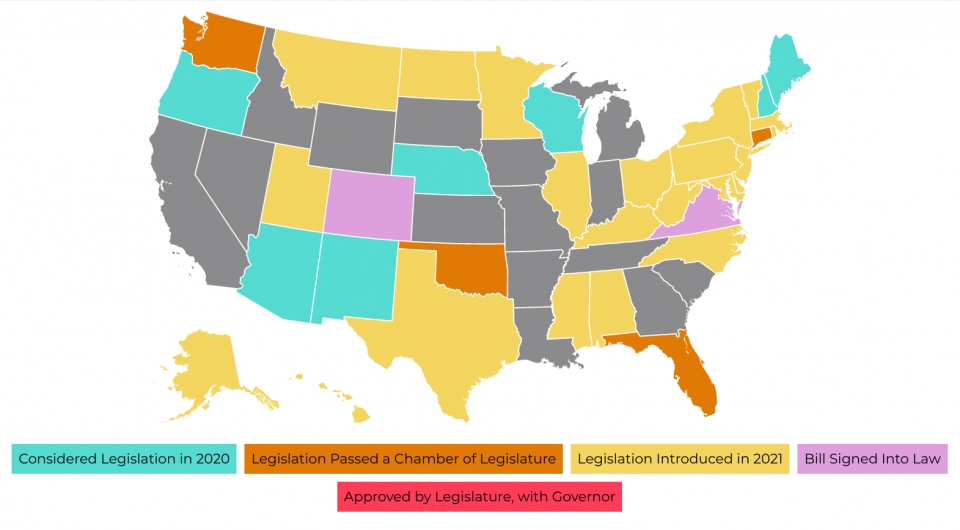

Why does this matter? Across the country, a patchwork of differing state data privacy laws is emerging, setting up a difficult compliance regime for small businesses. This year, Virginia and Colorado respectively adopted the second and third comprehensive privacy laws in the nation. States like Connecticut, Florida, Oklahoma, and Washington passed legislation in at least one chamber of their statehouses but failed because they included private rights of action. Another 22 states also considered bills. 2022 is also expected to be just as active a year in state capitals. California is also undergoing a major rulemaking this year to be completed by the new California Privacy Protection Agency, which will add to the requirements businesses already have to follow under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) estimated to cost small businesses $50,000 each to comply. A $1 billion enforcement bureau at the FTC with new privacy rules exacerbates this patchwork immensely.

The solution is simple—Congress should enact a national privacy law that protects all Americans equally, regardless of where they live and do business. There should be one clear and robust set of rules established by Congress and not by regulatory agencies assuming powers without appropriate guardrails.

The Commission has established itself as the expert data protection agency in the United States, but funding and rulemakings for privacy at the Commission should be authorized by bipartisan, comprehensive legislation. The Chamber supports Representative Suzan Delbene’s (D-WA) Information Transparency & Personal Data Control Act, which gives the Commission reasonable rulemaking authority, increase funding and staff, and leaves enforcement to the Commission and state attorneys general.

Congress must affirmatively work to give consumers control of personal data and prevent a federal and state patchwork that confuses consumers and harms small businesses.

The Weekly Download

Subscribe to receive a weekly roundup of the Chamber Technology Engagement Center (C_TEC) and relevant U.S. Chamber advocacy and events.

The Weekly Download will keep you updated on emerging tech issues including privacy, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, transportation, and government digital transformation.