C_TEC Testimony Against North Dakota HB 1330 on Data Privacy

ON: HB 1330 Data Privacy Bill

TO: North Dakota House Industry, Business & Labor Committee

DATE: February 9, 2021

BEFORE THE NORTH DAKOTA HOUSE INDUSTRY, BUSINESS & LABOR COMMITTEE

Hearing on HB 1330 Data Privacy Bill

Testimony of Jordan Crenshaw

Executive Director & Policy Counsel, Chamber Technology Engagement Center

February 9, 2021

Good morning, Chairman Lefor and Vice Chairman Kesier, and members of the Committee. My name is Jordan Crenshaw and I am the Executive Director & Policy Counsel the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Technology Engagement Center (“C_TEC”). C_TEC was established to promote the role of technology in our economy and to advocate for rational policies that drive economic growth, spur innovation, and create jobs.

At issue today is HB 1330, a proposed data privacy bill that would require all kind of companies to obtain consent before selling personal information to be enforced by potential class action lawsuits. HB 1330 comes at a time when a patchwork of state privacy laws is emerging which threatens to create confusion for both consumers and business, particularly small enterprises. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce supports national privacy legislation that protects all Americans equally and discourages state legislation that could create regulatory uncertainty by imposing enforcement mechanisms like private rights.

I. DATA IS ESSENTIAL TO THE 21ST CENTURY ECONOMY

First, I would like to note that data is transforming our economy and has been vital in keeping the “digital lights on” for many companies, particularly small businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic whether that be through contact tracing, enabling faster distribution of PPP loans by fintech companies, or helping Americans stay connected through remote work, ecommerce, online learning, and telehealth.[1] Prior to the pandemic, C_TEC released a report which showed that even as the number of data breaches increases, identity theft is holding at around the same levels. This is in part due to data being used to identify fraud and stop it in its tracks.2 We’ve also found that data used by the private sector is helping protect citizens from wildfires, promote financial inclusion, and enhance public safety. Private-sector data enabled law enforcement to locate and stop the San Bernardino mass shooter during his spree.[2]

What these examples show is that data is necessary to a functioning 21st century society. Privacy legislation should include exceptions for important societally beneficial purposes such as anti-money laundering and fraud protection, research, and commercial credit reporting. Unfortunately, HB 1330 provides NO exceptions to its privacy requirements.

II. The Growing State Patchwork

a. California

A growing patchwork of state privacy legislation and laws currently threatens the ability of companies like retailers, manufacturers and small businesses to innovate and offer services to their consumers. In 2018, California passed the nation’s first sweeping privacy legislation.[3] Among rights to access data and deletion, the CCPA gives consumers the right to opt out—not opt in—of data sales.

Prior to implementation of CCPA, the State’s Attorney General commissioned a study to determine the economic impact its proposed regulations would have on California. According to the study, CCPA regulations could cost State businesses a total of $55 billion in compliance costs. For businesses with 20 or fewer employees, the regulations are expected to cost small businesses up to $50,000. These costs do not include potential lost revenue or heightened costs from having to administer a complex compliance system that addresses conflicting state laws.

Also, California’s law does not include a private right of action to enforce its privacy provisions which would further skyrocket economic costs. Californians recently adopted the California Privacy Rights Act, which will become effective in 2023 and will add further costs.

b. Other States

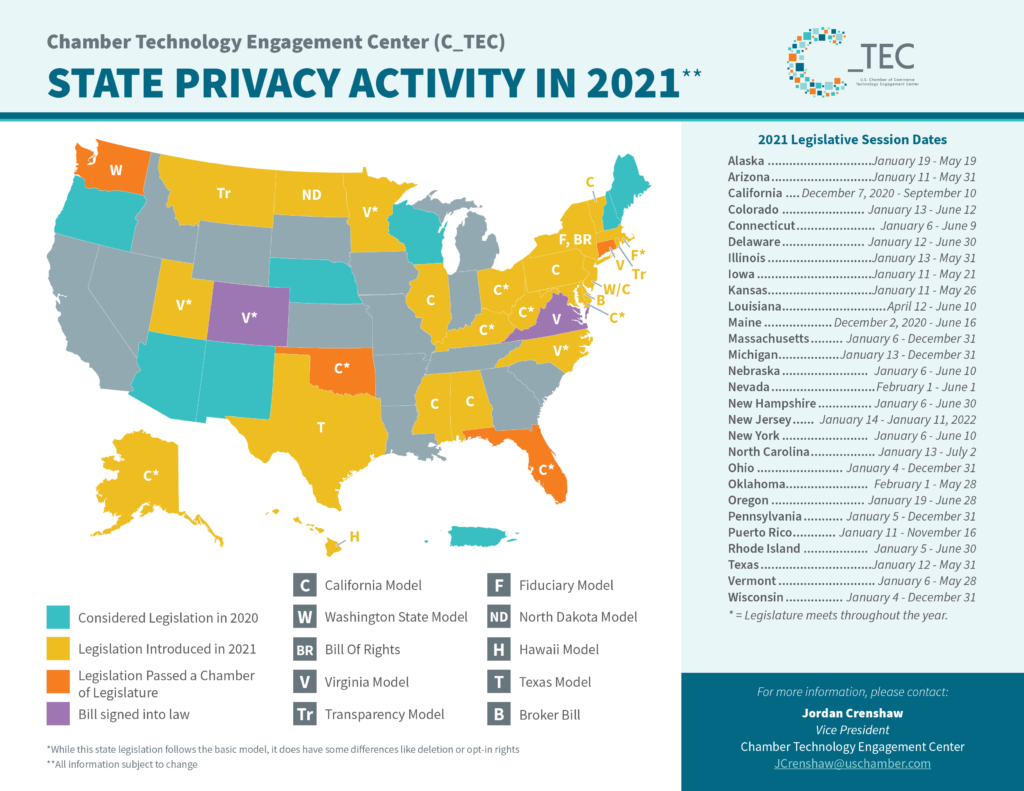

Various state models are currently emerging that could create confusion for Roughrider

State consumers and companies doing business across state lines. Several models are emerging[4]:

- Washington Model: The “Washington Privacy Act” would give consumers the right to access, correction, deletion, and opt out of processing data for targeted advertising, data sales, and profiling in furtherance of decisions producing a legal effect. Controllers must issue a privacy notice, limit collection and use, and maintain reasonable security. The Attorney General would be tasked with enforcement and the Act would not give rise to a new private right of action. A previous version of the bill nearly passed in 2020 but was defeated because lawmakers in Olympia attempted to pass a private right of action. Lawmakers this year in Virginia overwhelmingly have voted to pass a similar bill.

- Fiduciary Model: Among other requirements, the fiduciary model imposes a duty upon companies not to process data in a way that is harmful to consumers.

- Bill of Rights Model: Being considered in New York, this model would task the Secretary of State through rulemaking to develop a Privacy Bill of Rights including but not limited to the right to data protection, access, correction, deletion, control, and opting out of sales. A new Data Privacy Advisory Board would provide guidance.

- Hawaii Model: This model would require opt-in consent only for internet browser history and location data.

One major takeaway from the various state models is that all the major models neither impose a strict opt-in regime for data sharing nor do they lack exceptions for societally beneficial uses of data. Additionally, California voters approved privacy rules solely enforced by government agencies and legislators in both Washington State and Virginia have rejected private rights of action.

III. Federal Legislation

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill in Washington are also considering national privacy legislation. Most of the privacy bills offer the rights of access, transparency, deletion, and even correction of personal information. Proposals from Republican Senators Roger Wicker (R-MS) and Jerry Moran (R-KS) do not have blanket opt-in requirements that lack permissible uses of data. For example, Senator Wicker’s SAFE DATA Act only requires opt-in for sensitive data. Both Republican bills reject a private right of action and create a national privacy standard.[5] Democratic proposals though, except for legislation by Rep. Suzan Delbene (D-WA), would enforce privacy through private rights of action.[6] Even these Democratic proposals, although relying on opt-in for sensitive data recognize the importance of exceptions for legitimate uses of data.

IV. U.S. Chamber Principles for Privacy Legislation

To encourage consumer protection, instill business certainty, and promote innovation, C_TEC calls on Congress to pass national privacy legislation that gives consumers the right to know how data is used, collected, and shared; delete personal information; and opt out of the sharing of personal data that does not have a legitimate purpose. Rights to delete and opt out should take into consideration a business’s need to retain and use information as necessary to conduct operations and meet other state and federal requirements such as record retention laws. Privacy legislation should focus solely on personal information that directly identifies a person or can reasonably be used to identify a person.

National Privacy legislation should among other things incorporate the following principles[7]:

- One National Framework: Consumers and business benefit when there is certainty and consistency regarding regulations and enforcement of privacy protections. They lose when they must navigate a confusing and inconsistent patchwork of state laws.

- Risk-Focused and Contextual Privacy Protections: Privacy protections should be considered in light of the benefits provided and the risks presented by data and by the manner in which it is used. These protections should be based on the sensitivity of the data and informed by the purpose and context of its use and sharing. Likewise, data controls should match the risk associated with the data and be appropriate for the business environment in which it is used. For instance, like the CCPA’s approach, personal information collected and otherwise used in an employment and business-to-business context should be exempted from the scope of a national privacy law.

A national privacy law should enable legitimate uses and promote uses of data that are a net societal benefit and should not hamper critical data processing. For example, privacy legislation should:- Permit commercial credit reporting, a service which can be a lifeline for small businesses during COVID-19.

- Respect First Amendment-protected activities and not inhibit the use and sharing of publicly available data.

- Facilitate activities to combat malicious or illegal activity like financial crimes, fraud, identity theft, and money laundering; prevent shoplifting; and mitigate security threats. The private sector should continue to be able to assist law enforcement address violations of federal, state and local laws.

- Transparency: Businesses should be transparent about the collection, use, and sharing of consumer data and provide consumers with clear privacy notices that businesses will honor. Legislation should not cause the required level of transparency to undermine or eliminate existing trade secret protections.

- Enforcement Should Promote Efficient and Collaborative Compliance: Consumers and businesses benefit when businesses invest their resources in compliance programs designed to protect individual privacy. In order to provide certainty and utilize alreadyexisting expertise, federal data privacy legislation should not be enforced by newly created data protection agencies.

Congress should encourage collaboration as opposed to an adversarial enforcement system. A reasonable opportunity for businesses to cure deficiencies in their privacy compliance practices before government takes punitive action would encourage greater transparency and cooperation between businesses and regulators. In order to facilitate this collaboration, a privacy framework should not create a private right of action for privacy enforcement, which would divert company resources to litigation that does not protect consumers. Enforcement authority should belong solely to the appropriate federal or state regulators.

According to a report by the U.S. Chamber’s Institute for Legal Reform, a private right of action would have negative impacts and [8]:- Undermine appropriate agency enforcement and allow plaintiffs’ lawyers to set policy nationwide, rather than allowing expert regulators to shape and balance policy and protections

- Result in inconsistent and dramatically varied, district-by-district court ruling

- Lead to grossly expensive litigation and staggeringly high settlements that disproportionately do not benefit individuals whose privacy interests may have been infringed

- Hinder innovation and consumer choice by threatening companies with frivolous, excessive, and expensive litigation, particularly if those companies are at the forefront of transformative new technology.

V. CONCLUSION

Consumers deserve to have their privacy protected in addition to reaping the health, financial, and safety benefits data provides to society. For these companies to most successfully innovate consumers must trust personal information is protected and not have to navigate a confusing patchwork of laws to enforce their privacy rights. It is for this reason that the Chamber believes one robust federal law that protects all Americans equally, enables beneficial uses of data, and is enforced by a clearly identifiable government agency is the correct approach. Thank you for your time and the Chamber is ready to assist as North Dakota continues to consider privacy legislation.

[1] America’s Next Tech Upgrade: Data For Good and the Need for a National Data Strategy, C_TEC (Oct. 21, 2020) available at https://americaninnovators.com/wp–content/uploads/2020/10/CTEC_TechUpgrade_Data_.pdf. 2 Data Flows, Technology, & the Need for National Privacy Legislation, C_TEC (July 11, 2019) available at https://americaninnovators.com/research/data–flows–technology–the–need–for–national–privacy–legislation/.

[2] Data for Good: Promoting Safety, Health, and Inclusion, C_TEC (Jan. 30, 2020) available at https://americaninnovators.com/wp–content/uploads/2020/01/CTEC_DataForGood_v4–DIGITAL.pdf.

[3] Cal. Civ Code § 1798.100 et al.

[4] https://americaninnovators.com/news/2021–data–privacy/

[5] https://americaninnovators.com/wp–content/uploads/2020/10/CTEC_RepFedPrivacyProposals_v1–1.pdf.

[6] https://americaninnovators.com/wp–content/uploads/2020/10/CTEC_RepFedPrivacyProposals_v1–1.pdf

[7] U.S. Chamber Privacy Principles available at https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/023546_ctec_data_privacy_principles_one_pager_02_2019.pdf.

[8] https://instituteforlegalreform.com/research/ill–suited–private–rights–of–action–and–privacyclaims/

The Weekly Download

Subscribe to receive a weekly roundup of the Chamber Technology Engagement Center (C_TEC) and relevant U.S. Chamber advocacy and events.

The Weekly Download will keep you updated on emerging tech issues including privacy, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, transportation, and government digital transformation.